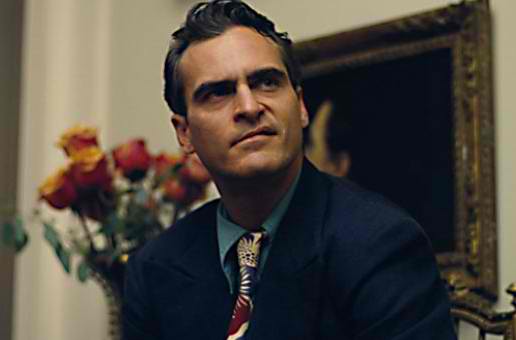

If P.T. Anderson’s previous drama, There Will Be Blood, was about two men who see each other for exactly who they are, his new film, The Master, shows us two deeply broken men trying to escape from themselves. The master, it turns out, is neither Joaquin Phoenix as troubled World War II veteran, Freddie Quell (with a name as conspicuously metaphorical as Daniel Plainview or Eli Sunday), nor Philip Seymour Hoffman as writer, doctor, nuclear physicist, and theoretical philosopher, Lancaster Dodd. The master, in fact, is not really a person at all, but a driving force that will please those who take amusement in invoking Sigmund Freud in the name of sexual dysfunction. Dodd is subtle and insinuating while Quell is overt and threatening. Phoenix wears an ever-present sneer and too-big clothing over his emaciated frame, imbibing his character with as much commitment as Daniel Day Lewis in Blood, while Hoffman prances through the film with so much polish on his performance that after a while his entire character starts to feel like a put-on. Perhaps that is the point. Only in two or three instances is the real man allowed to seep through, sometimes explosively, and then only briefly.

There is some deeply troubling subtext, to be sure. Perhaps a bit too subtle to be engaging and too often diverted by unfulfilled subplots. Conflicts are introduced and then immediately abandoned. Those looking for a hard-hitting obloquy of Scientology will come away empty. The parallels between the controversial religion and this film’s The Cause are merely superficial.

The Master lacks the lyricism and melodrama that made the one-two punch of Magnolia and Punch-Drunk Love pack such a wollop, and was even present in the taut strains of There Will Be Blood. Anderson adopts a more direct, somber tone here, reflected in Johnny Greenwood’s uneven score. The drifting, passionate movements of Jon Brion are sorely missed. The overall impression one is left with is that the director seems unable to commit.

See instead: Midnight Cowboy (1969). If you’re going for tragic, go whole hog. More overtly sexual, John Schlesinger’s moving examination into the lives of two con men is touchingly, platonically romantic, with one of the saddest endings in motion picture history.

It’s easy to conclude from cinematographer-cum-director Ron Fricke’s new non-narrative documentary, Samsara, that humanity is a degenerate wretch. The beauty of nature that usually opens his films is inevitably countered by trash-scrounging indigents, gun-wielding militaries, dancing convicts, the sex trade, and the cold, cruel efficiency of automated animal farming. Fricke covers a lot of the same ground as his previous film, Baraka. So much so that this could almost be considered a remake. Some of the shots are identical and one could be forgiven for thinking them recycled. Fricke takes his time to draw the audience in, not revealing his true purpose until well into the proceedings before you realize you’ve been hooked. Where on Baraka he wielded a mallet, here he swings a sledgehammer. The results are nothing short of potent.

Goes great with: Baraka (1992). A great way to draw comparisons, it also highlights how little things have changed in the last two decades.

Disagree? That’s fine by me. Share your thoughts below.

You must be logged in to post a comment.